A New Paradigm of Risk Management For Thyroid Cancer

This article is intended to informed someone that is dear to my heart and was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in Mainland China this year, after which she underwent surgery. Of course, I am not a medical doctor, I am a biophysicist, and this is not medical advice, but an overview of the current guidelines in relation to the diagnosis, treatment, as well as prognosis of the disease. The main focus will be on overdiagnosis and overtreatment of low-risk thyroid cancer.

As a primary reference I will follow the 2015 American Thyroid Association (ATA) Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer [1], as well as the National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer 2022 in China (English version) [2], alongside The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes [3].

Prevalence of thyroid cancer found in autopsy studies:

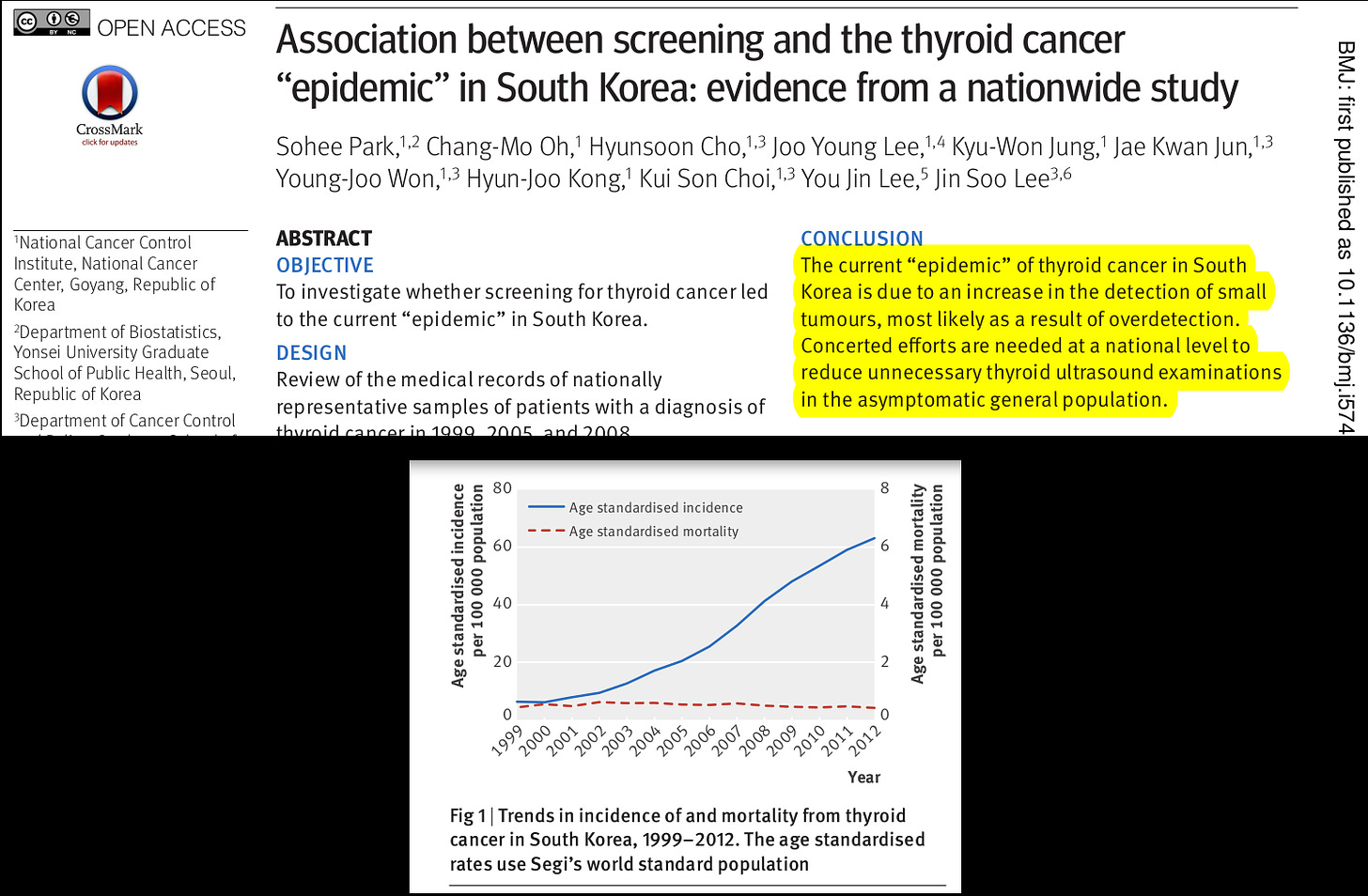

Autopsy studies are of critical importance to put into context the current increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer, especially among young adults, that has simultaneously emerged globally during the last decades, while no increase on mortality related to the disease has been associated with it. Widespread use of UltraSonography (US) and US-guided Fine-Needle Aspiration (FNA) biopsy seem to be the main factors behind this current “epidemic” [4][5][6][7].

Figure 1: The Thyroid Cancer Epidemic, 2017 Perspective [4].

Figure 2: Association between screening and the thyroid cancer “epidemic” in South Korea: evidence from a nationwide study [6].

Figure 3: Cancer Screening, Overdiagnosis, and Regulatory Capture [7].

Following systematic autopsy studies, like the one performed by Finnish pathologists in 1985 [8], where a prevalence as high as 36% of specimens containing papillary thyroid cancer was found, one can start to realize, as the authors pointed out in their conclusions, that low-risk thyroid cancers “can be regarded as a normal finding”. A Recent Meta-Analysis study (year 2016) [9] indicated an incidental finding of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer (iDTC) upon autopsy of 4%-11%, where the “prevalence of iDTC among the partial and whole examination subgroups was 4.1% (95% CI, 3.0% to 5.4%) and 11.2% (95% CI, 6.7% to 16.1%), respectively”. A review of the same study was presented by the ATA [10], highlighting “that the rate of thyroid cancer in an autopsy specimen was dependent on how thoroughly a thyroid specimen was examined”. The main conclusion was that the prevalence has not increase since 1970. Hence, overscreening via US and US-guided FNA in asymptomatic patient is very likely responsible for the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of a large number of subclinical diseases that are generally present within the population, without ever manifesting as an illness in the vast majority of the general public due to its primarily indolent nature. According to the Finnish team [8] Occult Papillary Carcinoma (OPC) “should not be treated when incidentally found”.

With regards to the finding of general thyroid nodules upon autopsy, some authors have observed a prevalence as high as 13%-60% (year 2009) [11] for thyroid nodules without clinical significance. In this case however, we have to remember that the nodules were not confirmed by pathologists and were not classified as benign, indeterminate, or malignant.

New guidelines intended to reduce the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of low risk thyroid cancer:

The National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHCPRC) [2] clearly states that "screening for thyroid carcinoma in general population without risk factors is not routinely recommended". At the same time in the 2015 ATA guidelines [1] they remarked that "screening programs for patients at risk of oncological disease are usually advocated", where one of the conditions to these particular high-risk cases is "a clear demonstration that the patient is indeed at risk". In many respects both guidelines seem to be in agreement. Additionally "in 2017 the United States Preventative Services Taskforce (USPSTF) gave thyroid cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals a grade of “D,” which means a recommendation against screening" [4].

Regarding when to perform a US-guided FNA once a thyroid nodule has been clinically or incidentally discovered "major guidelines for thyroid nodule management recommend against general biopsy of nodules <1 cm in size" ([4]; [1][2]). To this particular point the NHCPRC guideline [2] makes the following reasonable assessments that can lead to the discovery of a rare case of aggressive thyroid cancer. "Unless the following conditions: A) abnormal cervical lymph nodes observed; B) history of neck radiation exposure or exposure to radiation contamination in childhood, family history of thyroid cancer or history of thyroid cancer syndrome; C) positive lesions in 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose, 18F-FDG); or D) abnormally elevated serum calcitonin levels."

With respect to the Bethesda system [3] in reporting FNA cytolgy, where 60%–70% samples are reported as definitively benign, 2%–5% as definitively malignant, and the remaining samples are cytologically indeterminate, including AUS/FLUS in 1%–22% of nodules, FN in 2%–25%, and SFM in 1%–6% [1][3]; major changes are happening in the reclassification of some of the subtypes of papillary thyroid cancer as it is the case for the now called Non-Invasive Follicular Thyroid Neoplasm with Papillary-Like Nuclear Features (NIFTP) [3], since 2016 [4], that is, non-cancerous. In this regard, the acknowledgment within the recommended guidelines of avoiding biopsies of nodules <1 cm in size are pushing Papillary Mycrocarcinomas towards a similar reclassification in the near future, due to their mostly indolent nature [12]. A comprehensive short clip on this topic can be found here ([13], see video below), where author Juan Brito, M.B.B.S., was already considering the importance of this issue in 2013.

Another indication of this trend is the acknowledgment of an alternative to surgery, called active surveillance. Within the NHCPRC guideline [2] "low-risk papillary microcarcinoma. Because of its slow progression and low lethality, conservative therapy, i.e., active surveillance, can be considered", within the limits of the following risks factors "1) the primary tumor is a single lesion; 2) the primary lesion is <1 cm in diameter; 3) the location of the primary lesion is in the central part of the thyroid gland rather than adjacent to the border of the thyroid gland or trachea; and 4) there are no regional lymph node metastases by evaluations". Similar recommendations can be found, with some differences, within the 2015 ATA guidelines [1] followed by a more recent statement in their short report on Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid Gland from 2018 [12], "since the vast majority of thyroid microcarcinomas will not cause any health risks during the patient’s life, doctors believe that there are 2 correct approaches to managing these tumors: surgical excision versus active surveillance."

Important Considerations of risk following the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology [3]

Starting with the indeterminate cytological samples, both the Atypia of Undetermined Significance/Follicular Lesion of Undetermined Significance (AUS/FLUS) "have a lower risk of malignancy, warranting separation from the other two indeterminate categories". With regards to molecular testing "Mutational testing for AUS/FLUS exhibits low sensitivity for the BRAF V600E mutation alone, reflecting the observation that malignancies identified from the AUS/FLUS category are low risk relative to the malignant and suspicious for malignancy categories".

Within the Follicular Neoplasm/Suspicious for a Follicular Neoplasm (FN/SFN) category there exist a clear impossibility of distinguishing adenoma from carcinoma via FNA alone and it is recognized that most cases end up being adenomas instead of follicular carcinomas due to the proportions within the population. Although "not all the malignancies prove to be follicular carcinomas: many if not most of the malignancies (27–68%) are interpreted histologically as papillary thyroid carcinoma". "The likelihood that the nodule is neoplastic is 65–85%. The rate of malignancy is significantly lower, at 25–40%."

Finally the third category of indeterminate cytological samples, the ones that are Suspicious For Malignancy (SFM) have relatively high rate of malignancy and their management may depend on the type of Thyroid Cancer that is suspected. "Historically, there has been limited utility for ancillary molecular studies for an “SFM, suspicious for Papillary Thyroid Cancer (PTC)” FNA diagnosis", however it may be very helpful for the more aggressive types "for patients with the diagnosis “suspicious for Medullary Thyroid Cancer (MTC)” or “suspicious for lymphoma”". Suspicious sonographic features as well as clinical symptoms may be considered in order to stablish a predictive prognosis.

With regards to the malignant category, MTC is presented in 1%-2% of all thyroid carcinomas and are more aggressive and less differentiated than papillary or follicular cancers. Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma (PDTC) accounts only for 0.3–6.7% of all thyroid cancers and "tend to metastasize to regional lymph nodes, lung, and bones" and has a poor clinical prognosis. Undifferentiated (Anaplastic) Thyroid Carcinoma (UTC) represent less than 5% of all thyroid cancers and are rarely seen in patients less than 50 years of age. In this rare and aggressive type of cancer "Most patients succumb to their disease within 6 months to 1 year of the initial diagnosis".

Finally, in the malignant category, the most frequent type of Thyroid Cancer is PTC, accounting for 85% of all cases, of which "more indolent forms of PTC are increasingly diagnosed" while more aggressive subtypes have become rare in comparison.

The case for Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinomas (PTMCs)

While PTMCs accounted for 25% of all thyroid cancer in 1988, the percentage reached 39% in 2008 and 47.5% in 2016 [14]. Therefore it can be considered as the main driver of the increase in the incidence of thyroid cancer worldwide and the main source of the "epidemic of diagnosis" [14]. One could ask however, how is it possible, given the new guidelines that recommend against US-guided FNA for Thyroid nodules < 1cm, which is the exact definition of a Microcarcinoma (less than 1cm) [12]. However, it seems to be, and this is a key point in the whole presentation that "once a small thyroid nodule is detected, regardless the method of detection, some clinicians would perform an FNA biopsy despite the recent ATA guidelines recommendation against performing biopsies of small thyroid nodules. In a recent survey study, 67% of the responders said they would perform an FNA in a thyroid nodule <1 cm with suspicious sonographic pattern" [15]. One could argue that this is one of the major challenges within the field.

As an extension to the case for PTMCs risk management it is appropriate to review some of the literature with regards to sonographic features and prognosis. One of the conditions within the NHCPRC guideline [2] in order to consider active surveillance is that we have a solitary nodule, once malignancy has been determined. However as we saw in the previous section the process for reporting thyroid cytopathology is not always straightforward and there is the possibility of misclassification within several gray zones that overlap with each other. In this respect one study reported no difference in the likelihood of thyroid cancer independently of the number of thyroid nodules [16]. One would agree however that a location that can compromise surrounding important critical structures in the neck, as well as extrathyroidal extension, which is associated with negative clinical outcomes [17], and lymph node metastases (see next section) are very important factors to consider in order to assess risk and prognosis of the disease. Patient age is also a key consideration given the fact that the progression of PTMC is somewhat higher in younger patients, although it can be observed without immediate surgery with a net benefit for the vast majority of patients, since there is no increase risk during surgery if it is performed at a latest stage "after subclinical PTMC has progressed to clinical disease" [18].

In order to close this section we might want to explore the difficulties that arise when nodule size is considered as a predictor of cancer. It has been reported no increase in cancer risk beyond a 2 cm threshold, above which there is highest risk [19], while others considers a threshold at 4 cm [20]. The 2015 ATA guidelines [1] recommend as a weak recommendation with low-quality evidence to consider surgery in benign nodules > 4 cm after repeated FNA biopsies when it is causing compressive or clinical symptoms.

Important considerations in relation to Lymph Node Metastasis and Recurrence

Due to grouping of clearly distinct types of thyroid cancer and clearly distinct risk cohorts of the population, one can encounter a considerably high uncertainty in the reporting of Lymph Node Metastases (LNM). From an incidence of Central Lymph Node Metastasis (CLNM) of 33% in PTMC [21], to a range of 20%-66% [22], up to a range as wide as 30%-80% for overall PTC [23]. Interestingly, the range seems to be more concerning in papers where total thyroidectomy with prophilactic central neck dissection is considered, up to 40%-90% of PTC patients according to ref. [24], where they concluded "that routine prophylactic CLND is optimal for clinically negative [i.e. cN0 patients on first presentation] PTC patients, during their first treatment", which is also the conclusion in ref. [22], while ref. [21] considers that prophilactic lymph node dissection in cN0 patients remains controversial. In ref. [23] total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection is considered favorable treating young male patients with cN0 PTC, due to higher risk in that particular cohort. A more balanced approach to this issue can be found in ref. [25], where they report (same as ref. [21]) a tumor metastases to the cervical lymph nodes in 33% of patients, and conclude that preventive central lymph node dissection is still considered controversial. There is a need to remember, however, that there still is some risk of recurrence after total thyroidectomy + central neck dissection. In one study, after total thyroidectomy and central neck dissection, 4.5% of patients developed lateral lymph node recurrence [26], while at the same time, with a less invasive surgery, the 2015 ATA guidelines [1] reports loco-regional recurrence rates of 2%-6% following thyroid surgery without neck dissection. Both can be considered to be in the same range, although there is no one-to-one comparison with regards to many studies. Additionally they documented that "in properly selected low- to intermediate-risk patients (patients with unifocal tumors <4 cm, and no evidence of extrathyroidal extension or lymph node metastases by examination or imaging), the extent of initial thyroid surgery probably has little impact on disease-specific survival" [1].

In this regard it is important to consider the rates that have been observed during active surveillance. In a review report, ref. [27] low levels of nodal metastases are a usual finding (3.4%-3.8% at 10 years follow up). We have to remember however that in these cases we are within the group of low-risk PTC, which fortunately accounts for the vast majority of cases. Another systematic review and meta-analysis reports lymph node metastases of only 1.6% [CI, 1.1%–2.4%] at 5 years during active surveillance [28]. The 2018 ATA report [12] considers a "4% risk of the tumor spreading to lymph nodes around the thyroid at 10 years" in the case of PTMCs and the 2015 ATA guidelines [1] reports that 1.7% and 3.8% of patients at 5-year and 10-year follow-up showed evidence for lymph node metastases.

Another extremely important consideration is that PTMCs have less than 1 in 1000 risk of dying [12] and Lymph Node Metastases are not associated with a less chance of survival [29]. The 2015 ATA guidelines [1] states that "common to all of these studies is the conclusion that the effect of the presence or absence of lymph node metastases on overall survival, if present, is small". In this regard, some researchers are even starting to consider an Active Surveillance (AS) approach to cases where Lymph Node (LNs) Metastases have been found [30]. They concluded that "AS of small LNs could be a feasible alternative to immediate surgery in properly selected patients". Clearly a benefit/risk ratio should be established when we encounter within the literature something as worrisome as this: "Mazzaferri reported that extensive lymph node dissections were associated with hypoparathyroidism in 20% and an overall complication rate of 44%; yet recurrences were not prevented with a recurrence rate of 2% per year" [29].

For a broader approach to the complexity of the issue in relation to lymph node metastases in cancer in general one must review the absolutely fabulous contributions of Dr. Blake Cady. One of his favorite quotes was “regional lymph nodes are indicators, but not governors of survival” [31]. In one of his publications he clearly stated, that "none of the published risk group definitions indicate that lymph node metastases have a relationship to thyroid cancer survival" [32]. He also acknowledged that the absence of distant organ metastases in these cases is an indication of metastatic specificity. This understanding, in his opinion, "hopefully will help place the role of lymph node metastases generally and their surgical removal on a more scientifically and logically based understanding". "Thus, the future may allow us to abandon some aspects of our surgical or systemic attack on clinical cancer metastases such as lymph node removal" [32]. For a more general view in relation to other cancers see refs. [33][34].

This same problem, in relation to extremely aggressive measures has been acknowledged, as well, in a quite fascinating review article by Clive S. Grant, already referenced previously as ref. [29]. I quote:

"Disease relapse testing—fear

With the turn of the new millennium, it seemed that the goal of endocrinologists was to eradicate all detectable and potentially all molecular evidence of PTC disease. Intertwined in the development of this attitude were two new extraordinarily sensitive measures to detect miniscule disease: high-resolution ultrasound (US), and stimulated thyroglobulin (Tg)."

"... the fear on the part of physicians and patients alike that even miniscule amounts of cancer was extremely worrisome and required intervention".

Conclusion:

Less aggressive cancers require less aggressive measures and observation, instead of highly intrusive surgeries with a non-zero risk for side effects and bad outcomes. One however will encounter the following arguments:

i) Some low-risk patients will rapidly advance towards distant metastasis and fast progression of the disease, even if in rare cases. "In addition, following up and waiting for the diagnosis of malignancies to change before taking action, the patient-undefineds psychological pressure is undoubtedly enormous" [22], therefore surgery must be preferred to active surveillance.

ii) The complexity of using RAI (Radioactive Iodine) or Tg follow-up in lobectomy patients favors bilateral resection instead. [29]

iii) "Because lymph node metastasis can be present in 20% to 90% of patients with papillary cancer, a therapeutic central compartment neck dissection should be performed along with the total thyroidectomy when lymph nodes are clinically involved" [35]

Counterarguments

(IMPORTANT NOTE: These final points are not part of the review article but a personal assessment that I would apply to myself in case I was diagnosed - It is not medical advice for the general public and it is not necessarily supported by the medical literature, although some medical professionals may agree with these statements to some degree - In case you have been diagnosed with thyroid cancer consult with your medical doctor):

i*) As a hypothetical estimation that may not be far from reality, let's assume that 1 in 500 patients with a diagnosis of low-risk PTMC has a progression to severe disease and fast distant metastases. Argument i) states that in order to prevent that 1 in 500 case, you should permanently damage the healthy organ of 499 patients. In my personal estimation, that approach cannot be justified in any way and less aggressive measures as well as optimization in the process of characterization of low-risk thyroid cancer are absolutely required. With regard to the anxiety levels of the patients under active surveillance, the only solution is better information that must be provided to patients in order to reduce their concerns, instead of promoting active campaigns of fear.

ii*) This factor must be considered on a case by case bases, I don't think simple general statements can solve this issue. However in many cases of low-risk PTMC the detection of trace levels of serum Tg, that are not clinically relevant, are prompt to more anxiety and even overtreatment as a result of "potential" recurrence. This must also be considered in the equation and it favors lobectomy for low-risk patients, since "Serum Tg values are not useful in the follow up of DTC patients managed with lobectomy alone" [36]. In any case, following the 2015 ATA guidelines [1], lobectomy alone is generally recommended in most non-aggressive cases.

iii*) I think this argument has been sufficiently entertained in the previous section.

Final remarks:

For now I will leave out of the discussion the subjects of Radiofrequency ablation and the value of thyroglobulin in dynamic risk stratification. These important topics will be revisited in a future version of this same review article.

Additionally, I will add a short opinion letter on the possibility of adjuvant treatment via the use of Medicinal Mushrooms during the Active Surveillance phase, proposing this as a new approach that should be evaluated within adequately established Randomized Clinical Trials. I am clearly not of the opinion that you should just observed and do absolutely nothing to manage the issue, even if low-risk. Diet changes, physical exercise, life-style changes... are absolutely required for general health. I am also absolutely against the damage of a healthy organ for no justifiable reason.

REFERENCES:

[1] 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26462967/

[2] National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer 2022 in China (English version) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35873884/

[3] The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-60570-8

[4] The Thyroid Cancer Epidemic, 2017 Perspective https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5864110/

[5] Mapping overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer in China https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/landia/PIIS2213-8587(21)00083-8.pdf

[6] Association between screening and the thyroid cancer “epidemic” in South Korea: evidence from a nationwide study https://www.bmj.com/content/355/bmj.i5745

[7] Cancer Screening, Overdiagnosis, and Regulatory Capture https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/2626156

[8] Occult papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. A "normal" finding in Finland. A systematic autopsy study https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2408737/

[9] Prevalence of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer in Autopsy Studies Over Six Decades: A Meta-Analysis https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27601555/

[10] Prevalence of thyroid cancer found in autopsy studies has not increased since 1970 https://www.thyroid.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/ctfp/volume9/issue12/ct_public_v912_10.pdf

[11] Thyroid nodularity--true epidemic or improved diagnostics https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20405636/

[12] Microcarcinomas of the Thyroid Gland https://www.thyroid.org/wp-content/uploads/patients/brochures/microcarcinomas_thyroid_gland.pdf

[13] Mayo Clinic Study: High-Tech Imaging Contributing to Overdiagnosis of Low-Risk Thyroid Cancers

[14] Risk stratification of papillary thyroid microcarcinomas via an easy-to-use system based on tumor size and location: clinical and pathological correlations https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34171064/

[15] Factors Associated With Diagnosis and Treatment of Thyroid Microcarcinomas https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31415089/

[16] Are solitary thyroid nodules more likely to be malignant? https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22569012/

[17] Extrathyroidal extension predicts negative clinical outcomes in papillary thyroid cancer https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32682508/

[18] Patient Age Is Significantly Related to the Progression of Papillary Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid Under Observation https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24001104/

[19] Thyroid Nodule Size and Prediction of Cancer https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23275525/

[20] Risk of Malignancy in Thyroid Nodules 4 cm or Larger https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28181427/

[21] The incidence and risk factors for central lymph node metastasis in cN0 papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a meta-analysis https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27645473/

[22] The real world and thinking of thyroid cancer in China https://journals.lww.com/ijsoncology/Fulltext/2019/12000/The_real_world_and_thinking_of_thyroid_cancer_in.1.aspx

[23] Predictive Factor of Large‐Volume Central Lymph Node Metastasis in Clinical N0 Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Patients Underwent Total Thyroidectomy https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34094896/

[24] Prophylactic central lymph node dissection in cN0 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: A retrospective study in China https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26117203/

[25] A Narrative Review of Preventive Central Lymph Node Dissection in Patients With Papillary Thyroid Cancer - A Necessity or an Excess https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35847927/

[26] Lateral lymph node recurrence after total thyroidectomy and central neck dissection in patients with papillary thyroid cancer without clinical evidence of lateral neck metastasis https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27865362/

[27] Active surveillance for patients with very low-risk thyroid cancer https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32128446/

[28] Active Surveillance for Small Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31368412/

[29] Recurrence of papillary thyroid cancer after optimized surgery https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25713780/

[30] Active Surveillance of Small Metastatic Lymph Nodes as an Alternative to Surgery in Selected Patients with Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35876426/

[31] Remembering Dr. Blake Cady https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications/news-and-articles/cancer-programs-news/080323/remembering-dr-blake-cady/

[32] Regional lymph node metastases; a singular manifestation of the process of clinical metastases in cancer: contemporary animal research and clinical reports suggest unifying concepts https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17953417/

[33] Proliferation and Cancer Metastasis from the Clinical Point of View https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-60327-087-8_3

[34] Impact of axillary lymph node dissection on breast cancer outcome in clinically node negative patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19199349/

[35] Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Thyroid Cancer https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25964831/

[36] Value of thyroglobulin post hemithyroidectomy for cancer: a literature review https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33244886/